Dreaming in Reverse Engineering

Written by Jennie Chu

Every week at Holberton School, we are given 2-3 problem sets, which always include some advanced extra credit problems. In our fourth week, we were given an executable program, written in C, that accepts a specific password. Our task was to create a random password generator that returns credentials for the executable. The goal of this exercise is to introduce us to assembly and reverse engineering, a process where, given a piece of software, one attempts to recreate its source code. For this project, I used the GNU Project Debugger (GDB), which can disassemble a program into human readable assembly code.

My goals were to disassemble the Linux executable, determine the parameters by which the password is checked, and finally, to create a C program that randomly generates valid passwords. Learning to read assembly code seemed instrumental to this exercise, so that is what I set out to do first.

Using GDB and other tools, I was able to view the compiled assembly code and see what happens in the executable, step by step. I set breakpoints throughout the program and inspected how data stored in memory address registers was being manipulated. After spending the entire day trying to make out bits of assembly code through reading its hexadecimal outputs, I found the general format of the original source code.

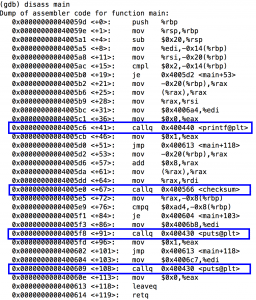

Using GDB, I first disassembled the main program to view the functions that were being called. I spotted two standard library functions, printf and puts, as well as a checksum function.

Using another tool, ltrace, I was able to see that there were two calls to the puts function, and that they returned “Access Granted” and “Access Denied” respectively.

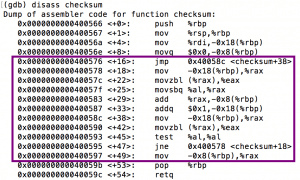

My next step was to examine the checksum function. After disassembling it, I saw that there is a loop that iterates through the password string, sums up each character’s ascii value, and stores the total on the stack. This suggests that the password’s parameters are dependent on the sum of input characters (more precisely, the ASCII codes of those characters).

However, nowhere in the checksum function does it compare my string’s sum to anything. Instead, the validation happens in the main function.

At address 0x4005e9, after the call to the checksum function, I can see a cmpq, a comparison instruction: It compares the checksum (stored on the stack) with the immediate value of $0xad4. This immediate value is represented in hexadecimal. (You know this because by convention, a number starting with 0x is a hexadecimal number.) When converted to base 10, it is 2772, so to get access to the executable, simply input a string whose characters’ ascii value totals 2772.

char array[63] = abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ0123456789

;

char password[100];

srand(time(NULL));

sum = 0;

i = 0;

while (sum < (2772 – 122))

{

r = rand() % 62;

password[i] = array[r];

sum = sum + password[i];

i++;

}

r = 2772 – sum;

password[i] = r;

Fourteen hours into this exercise, I finally had my random password generator. My program continuously appends a random alphanumeric character to an array until the sum of the characters is one alphameric from 2772, then appends a last character that completes the summation to 2772.

My logic was sound and all indicators suggested my output was correct. I double, triple, and quadruple-checked the string and its sum just to be sure, yet I was still denied access. It had been a long day (into the night), with my code untouched.

Laying in bed, I felt defeated. I’d spent so much time learning assembly code, which was by far the most difficult part of the assignment, but I couldn’t get my simple random password generator program to work. I fell asleep going through the logic of my code over and over again.

I dreamt about the day I’d had at Holberton, the lunch I ate, the people I talked to, and the day’s lessons about pointers and arrays. All the while, my password generator code was displaying in the background like some kind of teleprompter. And then I saw it: the null character—‘�’—a control character in C that signifies the end of a string. None of my randomly generated passwords contained a null character! So while the sum of the characters ended up at 2772, when my program tried to print the string, it wouldn’t know where to stop. It would try to read other blocks of memory, either currently used or filled with garbage, until it eventually found a null character.

At almost two in the morning, I woke up to this revelation. I had broken my glasses a few days earlier, so when I finally managed to find my laptop, I was literally squinting with my face inches from the screen, frantically typing away. When I made the changes and ran my revised program, it worked, and I was finally granted access.

I am currently a student at Holberton School, named after Betty Holberton, one of the first female computer pioneers. It is said that Betty would often dream about coding, and solved many problems in her sleep. Like Betty, my mind doesn’t stop when the workday ends at 5:00, or even during sleep. I hope to follow in Betty Holberton’s path, and make an impact in the programming field.

Jennie Chu was a former geologist and high school counselor and is now an aspiringFull-Stack Software Engineer, attending Holberton School in San Francisco. She is passionate about EdTech and dreams to make programming accessible to everyone.

About The Author

Jennie has always loved solving and tinkering with puzzles. Hoping to become the next Indiana Jones, she studied Geology and Archaeology. She was the first one in her family to graduate college and believes in equal educational opportunities. Eventually, she became a College Counselor for low-income and first generation college students to give back to her community before teaching herself web design. Jennie is now an aspiring Full-Stack Software Engineer, attending Holberton School in San Francisco. Jennie is passionate about EdTech and dreams to make programming accessible to everyone.